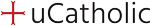

Imagine a day when altar boys became bishops, monks led wild dances, and hymns gave way to irreverent songs about donkeys.

Welcome to the Feast of Fools, a raucous medieval celebration that transformed cathedrals across Europe into scenes of hilarity and chaos. Rooted in ancient liturgical traditions, this peculiar festival turned the hierarchy of the Church on its head, sparking joy—and scandal—before the Church ultimately banned it.

Emerging in 12th-century France and celebrated primarily on January 1, the Feast of Fools embodied the biblical paradox of “the last shall be first.” It was a day for role reversals, where subdeacons—the lowest-ranking clergy—parodied their superiors in mock ceremonies. Choirboys might be crowned as “boy bishops,” and even a “Pope of Fools” could preside over exaggerated rituals. These antics symbolized humility, reflecting the idea that even the foolish and lowly are favored by God.

But what began as a symbolic and playful reminder of humility quickly spiraled into farce.

Participants donned masks, backward vestments, and comical costumes, chanting parodies of hymns and performing irreverent skits. Some clergy turned altars into gambling tables, rolled dice in the nave, or sang nonsensical prayers. In more extreme cases, animals were led into churches, including donkeys, which brayed as part of the spectacle.

The celebration often spilled into the streets, where townsfolk joined the revelry. Revelers in mud-smeared clothing, masked dancers, and cross-dressers mocked authority figures, including church leaders. Drunkenness and debauchery blurred the line between a festive inversion of norms and outright sacrilege.

As reports of excess and scandal grew, the Church sought to rein in the Feast of Fools. By the 12th century, theologians began condemning the practice. Church councils, including the Council of Basel in 1431, decried the feast as blasphemous, citing clergy dressed as minstrels, dancing in the choir and disrupting sacred rituals.

Efforts to suppress the festival varied. In some regions, the Church imposed stricter rules, toning down the revelry rather than abolishing it entirely. In others, the Feast of Fools was outright banned, though it persisted in some corners of France and Belgium into the 18th century.

Though officially suppressed today, the Feast of Fools left a lasting imprint on medieval culture. At its best, the feast was a reminder of humility and the biblical truth that God works through the lowly. At its worst, it devolved into a chaotic mockery of the very institutions it sought to uplift.

Photo credit: Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons